“The Casselman is coming back to life. It’s a gem of a river. It relies on rainfall and snowfall to run. It’s peaceful and healing. It has a different taste than all the other rivers, a different tone. It tells me: ‘Welcome. You can always come back to me, but I need to be protected.’”

“I have a deep love for the Casselman River. To me it’s sleepy. It’s mysterious. It’s underappreciated. I always say: ‘We don’t deserve the Casselman.’

“The Casselman was once a dead river. After the infamous blizzard of ‘93, the snow melted, and just outside Meyersdale there was a mining operation where they laid 1,000-feet of illegal piping that was draining abandoned mine water into an old mine void. Once the snow melted and filled the void to capacity, it created a mine blow-out. All those pollutants spilled into the Casselman and created a 42-mile fish kill. It’s a story that’s not often told.

“From the time I was a kid I knew I’d be the person to stand up for what I believed in and be noisy about it. But I felt like I got quiet over the years. I graduated college with a degree in interior design. And I started thinking: ‘What am I doing? I don’t want to keep people inside. It is to the core of me to encourage people to be outside.’ I eventually worked for about seven and a half years for the Laurel Highlands Visitors Bureau. Then as fate has played so many hands in my life, COVID happened. The travel industry took a hit, and I lost my job.

“I know this sounds cliche, but the rivers prepare you for stuff like this, to slow down. The whole time my husband and I were saying: ‘When in doubt, scout. Ride the wave. Be patient.’ I started job hunting again. Mountain Watershed Association offered me a job. That was it. And I ran with it. I knew this area from the tourism side, and I had talked about all the fun and adventure, but I also knew there was a threat that could impact the quality of the experience.

“Now I’m a community organizer. It is my job, my goal, my passion to rally the community against issues that could impact their health, their property, the environment, and our rivers. We have conservation efforts by way of treating abandoned mine drainage, water sampling, being satellite samplers for DEP, even to the recreation side of developing trails. So that’s my work, and it’s all woven into my personal deep, deep love for people and thriving communities and the rivers.

“The two biggest arguments for coal mining are jobs, and how else are we going to keep our lights on? And both are valid. I come from a family of coal miners. My grandfather was a coal miner. We’re not against the guy that’s trying to pay his bills, support his family, and create a good life. But we need to keep the companies who don’t live here in our rural community, who don’t need well water, who are likely making their decisions from an office somewhere else, we need to keep them accountable.

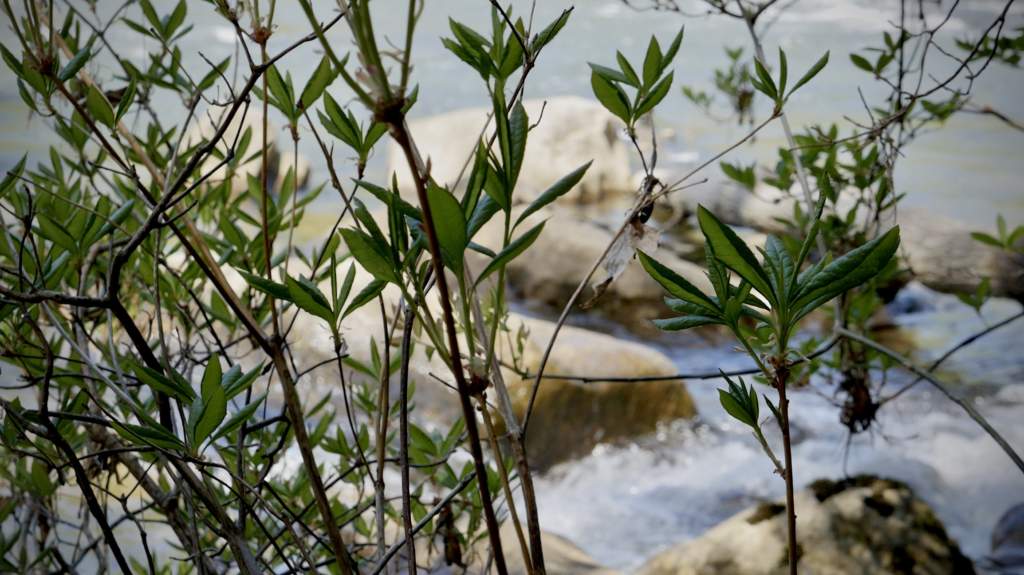

“Today the Casselman is coming back to life. It’s a springtime favorite. It relies on rainfall and snowfall to run. It’s peaceful and healing. It has a different taste than all the other rivers, a different tone. It’s this tucked away gem of a river that offers incredible scenery, wildlife, amazing fishing, and approachable whitewater rafting. It’s this magical, meandering piece of river with fascinating hemlock groves. It feeds into the Youghiogheny River and holds hands with the Great Allegheny Passage as it ribbons through the Laurel Highlands. The river and the trail are one.

“The Casselman tells me: ‘Welcome. You can always come back to me, but I need to be protected.’ If this place is polluted, who is going to come visit?”

This content was created by Anita Harnish for the Great Allegheny Passage Conservancy and financed through grants from the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources’ Bureau of Recreation and Conservation, through its Community Conservation Partnerships Program and Environmental Stewardship Fund, administered by Rivers of Steel Heritage Area and Pennsylvania Environmental Council’s Laurel Highlands Mini Grant Program; through funding via the Westmoreland, Fayette, and Somerset County Tourism Grant Programs; and with funds made available by the Great Allegheny Passage Conservancy.