“You can find so much meaning in nature by being observant to it, open to it. It’s always cycling.”

“One of the things I love about Dunbar Creek is that it demonstrates the resilience of a place. The lower reaches of Dunbar Creek, especially where it crosses under the Great Allegheny Passage into the Youghiogheny River at Connellsville, flow through a rather industrialized and residential zone. But the upper reaches, where it comes out of Chestnut Ridge, are quite remote and wild and almost pristine.

“There was a lot of strip mining that went on in the head waters, right around the time I was born. There were iron furnaces and coal mines, and all the timber was cut out at one time. It’s recovered to an amazing degree and there’s a great diversity of wildflowers, amphibians, and reptiles.

“There are some easily accessible parts of Dunbar Creek that are stunningly beautiful.

“These streams have been restored through expensive treatment facilities that have been built. It’s expensive engineering and there’s a life to those systems. There has to be a constant chasing of funding to both build these facilities and to maintain them.

“We think of fossil fuels as cheap energy. And they are cheap energy, as long as you don’t account for the costs that we’re trying to deal with today. When they dug out the coal in the 1950’s and in the seventies, it was cheap because they only figured in the labor, the fuel for the equipment, the depreciation of the equipment, the cost of the permits, those kinds of things. What they didn’t account for were the costs of a polluted stream, which IS a cost. Because if the community of Dunbar and everybody downstream has to, from now ever on, live with a polluted stream where nobody wants to come, nobody wants to be, nobody wants to spend money as a tourist, as a fisherman, then that’s a cost. There’s a cost to having these opportunities and these assets to enjoy.

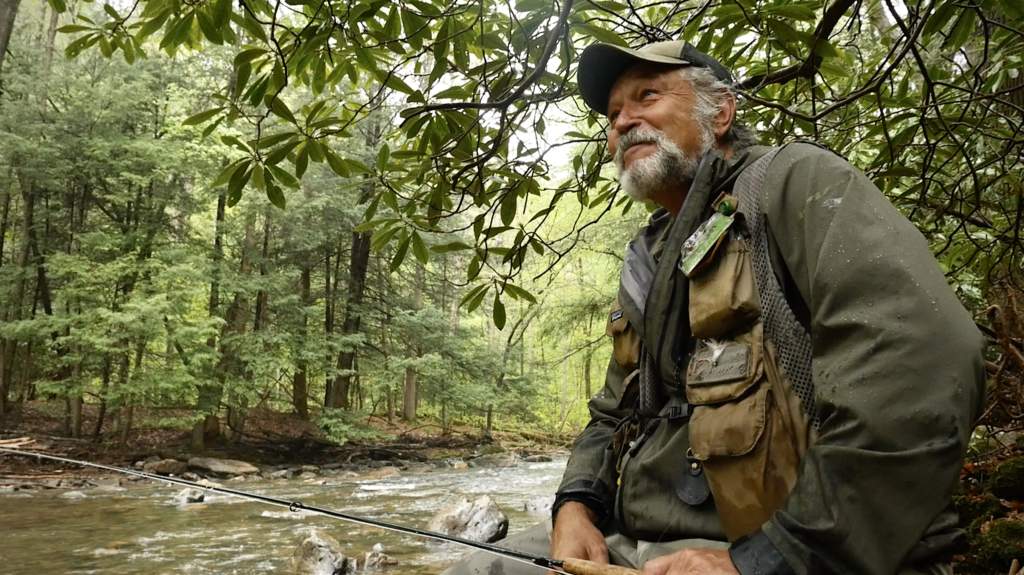

“Dunbar Creek is special to me. My dad and uncle took me fishing there when I was a young boy. I didn’t get to know my uncle very well but I knew that he was an esteemed outdoorsman, which to me was a prestigious thing. I was about four when my uncle let me hold the rod after he caught a trout. I still remember the hoopla of pulling that fish in.

I think that it’s going to be even more important going into the future to have an authentic experience that’s not provided by somebody else through some media. Even if it’s just picking a mushroom or catching a fish that you cook for a meal. Those are little circles that you can complete, if you know how to do it, because I think that people will become more insulated from nature than we are now.

I changed my professional life quite a bit in order to be in proximity to a lifestyle that put me in direct contact with nature every day. It was something that compelled me. A perfect day for me would probably involve fishing for trout somewhere on a little stream, but it wouldn’t necessarily be confined to that because I might wander off and look for wildflowers or take a nap in the sun.

You can find so much meaning in nature by being observant to it, open to it. I needed to be engaged with what was happening in the seasons. There’s always anticipation for something that’s coming up in the natural cycle of the year. Anticipation is very important in human happiness. And you have that if you’re attuned to nature. It’s always cycling.”

This content was created by Anita Harnish for the Great Allegheny Passage Conservancy and funded in part by a grant from the Community Conservation Partnerships Program Environmental Stewardship Fund, under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation administered through the Pennsylvania Environmental Council’s Laurel Highlands Mini Grant Program, and in part by the Somerset County Tourism Grant Program.